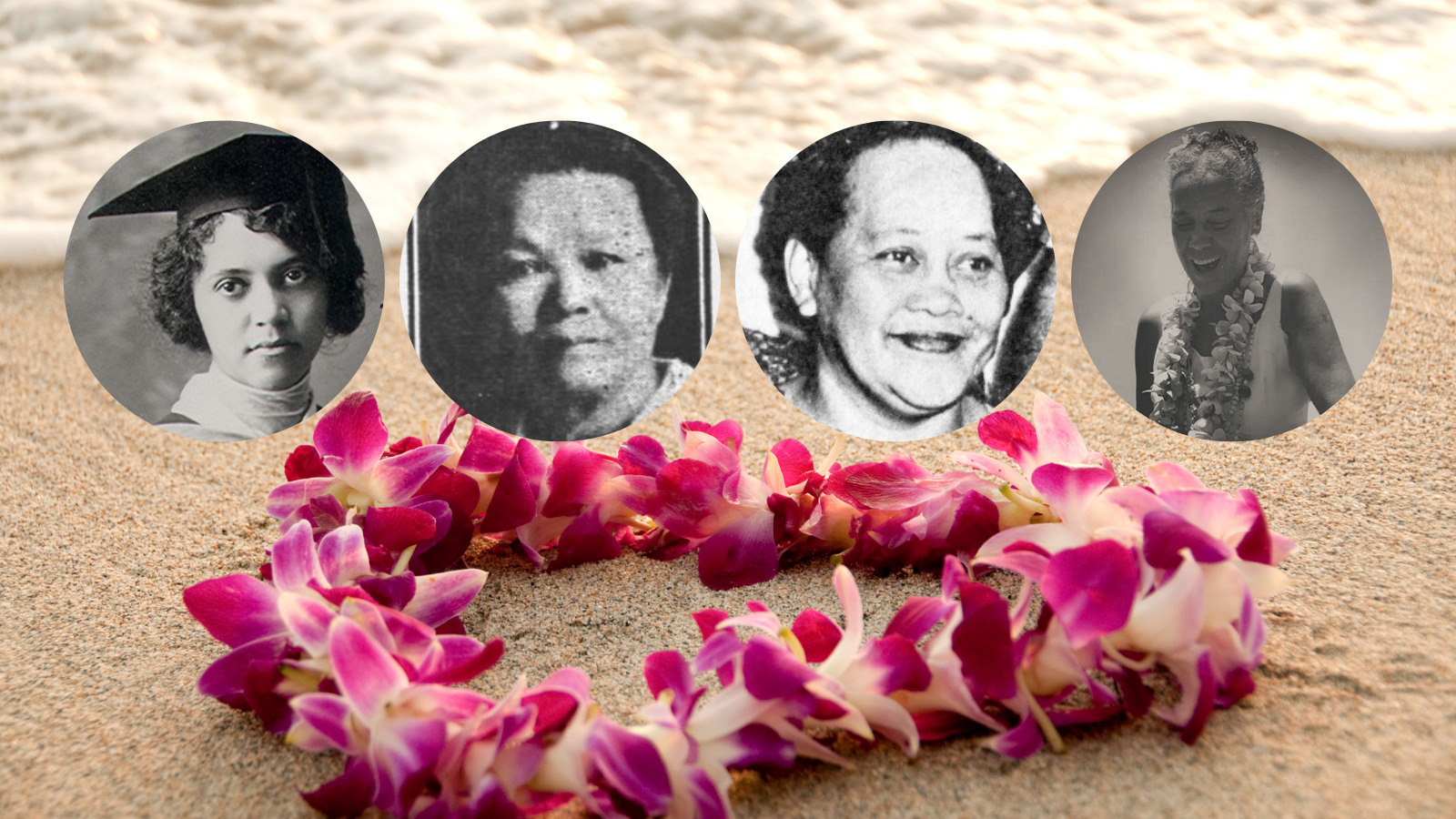

Wāhine in Hawaiʻi's History

March 13, 2024 Kawena Komeiji

March is Women’s History Month and we are celebrating wāhine in Hawaiʻi who have helped shape and create the world we know today.

Alice Ball

Alice Ball

Although Alice Augusta Ball was born in Seattle, WA, her family moved to Hawaiʻi for a year where she attended Keʻelikōlani School. Alice would return to Hawaiʻi for her master’s degree in chemistry. Her master’s thesis was about the chemical properties of ʻawa (or kava).

Because of her work, she was contacted by a doctor at the Kalihi Hospital for help treating leprosy. There, she developed an injectable version of chaulmoogra oil that was known to successfully treat the disease. Unfortunately, at the age of 24 in 1916, she would pass away before she could see the results of her invention.

Her advisor continued trials of the injectable oil and found major success, taking all of the credit for Ball’s work. Ball’s colleagues tried to correct public record and published a paper that included credit to Alice, but her former advisor was adamant that it was he who perfected the chaulmoogra oil injection.

It was not until the 1970’s that University of Hawaiʻi professors uncovered her work and fought to have her efforts recognized. In 2022, Governor David Ige declared February 28th as Alice Augusta Ball Day.

Resources

- Alice Ball: chemist who developed a treatment for leprosy – Georgina Ferry (article link; UH login required)

- Alice Augusta Ball: The African-American chemist who pioneered the first viable treatment for Hansen’s Disease – Sabha Mushtaq (article link; UH login required)

- Alice Ball – University of Oxford Museum of Natural History (article link)

Kong Tai Heong

Kong Tai Heong

Dr. Kong Tai Heong was born in Waichow, Guangdong, China in 1875 but was abandoned at an orphanage. The German nuns who had raised her helped her attend the Canton Medical School that taught Western medicine. There, she met her husband and they immigrated to Hawaiʻi in 1896.

In Hawaiʻi, both Dr. Kong and her husband were unable to practice medicine that they were trained in. Her husband, Li Khai Fai, worked in a factory job to make ends meet. Luckily, Kong Tai Heong met Reverend Frank Damon, who was able to convince Sanford B. Dole, President of the Republic of Hawaiʻi, to let both of them take a medical exam. They met with the Board of Medical Examiners and, with the assistance of an interpreter, they passed the oral examination and were granted licenses to practice medicine. Tai Heong focused most of her efforts on delivering Hawaiian and Portuguese babies. Because of her training in Western medicine, many in the Chinese community were wary of using her services.

In 1899, Dr. Kong’s husband, Li Khai Fai, suspected a case of bubonic plague in the Chinese community and reported it to the Board of Health. At the time, the most effective way to kill the bubonic bacteria was through fires. The Board of Health put Chinatown in quarantine and prepared for a controlled burn. Unfortunately, the winds shifted and the fire burned out of control, taking down many homes, businesses, and Kaumakapili Church.

After the fires, Li Khai Fai was ostracized from the Chinese community, who blamed him for the fires. Kong Tai Heong continued to deliver babies and had eight of her own. By 1946, it was estimated that she had delivered over 6,000 babies. She died in 1951 at the age of 76.

Resources

- Celebrating Dr. Kong Tai Heong, the first Chinese woman to practice Western medicine in Hawaiʻi – Lilian Tsang (Hawaiʻi Public Radio article link)

- Notable Women of Hawaiʻi – Barbara Bennett Peterson (print book link)

- Plague and Fire: Battling Black Death and the 1900 Burning of Honolulu’s Chinatown – James C. Mohr (ebook link, UH login required)

Helen Lake Kanahele

Helen Lake Kanahele

Helen Lake Kanahele was born in Kona, Hawaiʻi but lost both of her parents early in her life. She was adopted by Irene Woods who enrolled her into an E.K. Fernandez hula troupe that toured the world. Helen became involved in politics very early in her life, assisting the Democratic party with campaigning at the age of 12.

In 1948, Kanahele was living in the Papakōlea Hawaiian Homestead with her brother who was currently on strike for the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). When she went to support her brother and his colleagues, she became angry at seeing a counter-picket by the wealthy wives of business owners so in response, she made her own signs and picketed every day. Kanahele joined the women’s chapter of the ILWU and supported strikes by collecting donations and cooking food for the striking families.

With an understanding of how labor unions protect employees, Kanahele started organizing her unit at Maluhia Hospital into the United Public Workers union. This angered the management of the hospital who tried to re-assign her into the morgue, which she contested. Instead, Kanahele was transferred to Kalākaua Intermediate School.

In 1948, James E. Majors and John Palakiko were accused and convicted of murdering Theresa Wilder with a sentence of death by hanging. The community was divided on whether or not the death penalty was appropriate, especially given the similarities in this case with the Massie case. Kanahele and a colleague organized a petition with thousands of signatures from the community including Hawaiian homesteaders in Papakōlea, Nānākuli, and Waimānalo.

After years of delaying the death penalty, Governor Samuel Wilder King commuted Majors and Palakiko’s sentences to life in prison in 1954. Along with organizing and protecting laborer’s rights, Kanahele also had a hand in eliminating the death penalty from Hawaiʻi’s judicial systems during a time when women in leadership positions were not always accepted. Helen Kanahele Lake died in 1976 and is buried in Oʻahu Cemetary.

Resources

- Living Treasures of Hawaiʻi by the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaiʻi (print book link)

- Notable Women of Hawaiʻi – Barbara Bennett Peterson (print book link)

- The Reminiscences of Helen Kanahele – Helen Kanahele (only available in microfiche at UHM)

- Sisters Under the Skin: Diversity of Women and Labor in Hawaiʻi – Leslie Lopez (article link)

- The Lasting Significance of the Majors-Palakiko Case by Jonathan Y. Okamura (article link)

ʻIolani Luahine

ʻIolani Luahine

Born in 1915 in Napoʻopoʻo but raised in Kakaʻako, Harriet Lanihau Makekau was the hānai child of her grandmother’s sister, a dancer for Kalākaua’s court. As a baby, she fell ill and a kahuna told her family that her hānai mother needed to name her. From this moment on she was called, ʻIolani Luahine, and did not have that illness again.

She began training in hula at three years old and her hānai mother declared her, a hula kapu, which dedicated her life to hula and Laka (goddess of hula). This dedication guided her life and when her hānai mother found out that Kamehameha Schools forbade hula, she enrolled her at the Saint Andrews Priory School because they allowed students to dance hula. As a young girl, she performed for celebrities and tourists in Waikīkī but when her hānai mother died, she knew it was time to take hula in a more serious light.

At the University of Hawaiʻi, ʻIolani Luahine met Mary Kawena Pukui, who became her mentor. Together, they brought life back to traditional oli (chant) and hula. Many recalled that while watching ʻIolani Luahine dance, it was a spiritual performance in which she channeled the akua and ancestors. Some contend that ʻIolani Luahine also had mana kahuna with numerous examples of being able to alter the weather.

In 1946, ʻIolani Luahine opened her own hula studio and started teaching. Her students recalled that while strict, she was always pleasant and made you want to dance the correct way. Some of her students include Kawaikapuokalani Hewett and George Naʻope. Although she passed in 1978, her legacy continues with the ʻIolani Luahine Hula Festival and most importantly, through her haumāna (students) and their haumāna.

Resources

- Hula Hoʻolaule;a (streaming video link; UH login required)

- ʻIolani Luahine by Francis Haar (print book link)

- Keepers of the Flame: The Legacy of Three Hawaiian Women (streaming video link; UH login required)

- Living Treasures of Hawaiʻi by the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaiʻi (print book link)